Deep in the 80s, this possibility never occurred to me. The foreshadows of the Captain Britain Corps who turned up in the Alan Moore Captain Britain run – Linda McQuillan herself, Captain England, Captain Albion – suggest that the sheer multitude of Captains just riff on the CB identity with minimal fuss. We’re just meant to see the terms Britain and the UK as interchangeable, right? So CB and CUK are mirror identities, they map neatly onto one another.

But Britain is not altogether the UK. Britain is the landmass comprising England, Scotland and Wales; the United Kingdom is the political entity comprising England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. And it occurs to me that reading Captain Britain in the 80s in Northern Ireland might have been a very strange thing to do.

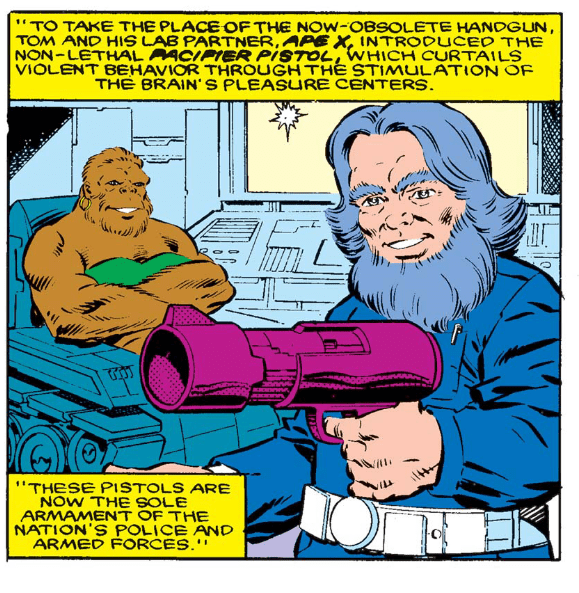

If Chris Claremont had been writing CB in the 80s, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. If there’s one thing Chris knows, it’s that an accent can do a lot of heavy lifting. In fact, in the right hands, an accent can do at least 60 per cent of your characterization, nein, katzchen? So if Claremont had been the writer, and he’d wanted to make CUK (Northern) Irish, he’d have dialled it up to maximum Banshee, and we wouldn’t have any doubts.

Moore and Delano? No such luck.

Instead, all we have is a coincidence: the surname McQuillan, which Wikipedia tells me, is not only Irish but that Mc (not Mac) is the “Ulster variant.”

Even if we’re not playing the Claremont accent game – even if we don’t hear Linda speak with a Northern Irish accent, we can certainly say that she is of Northern Irish parentage, or ancestry.

Does this do anything to our experience of the character?

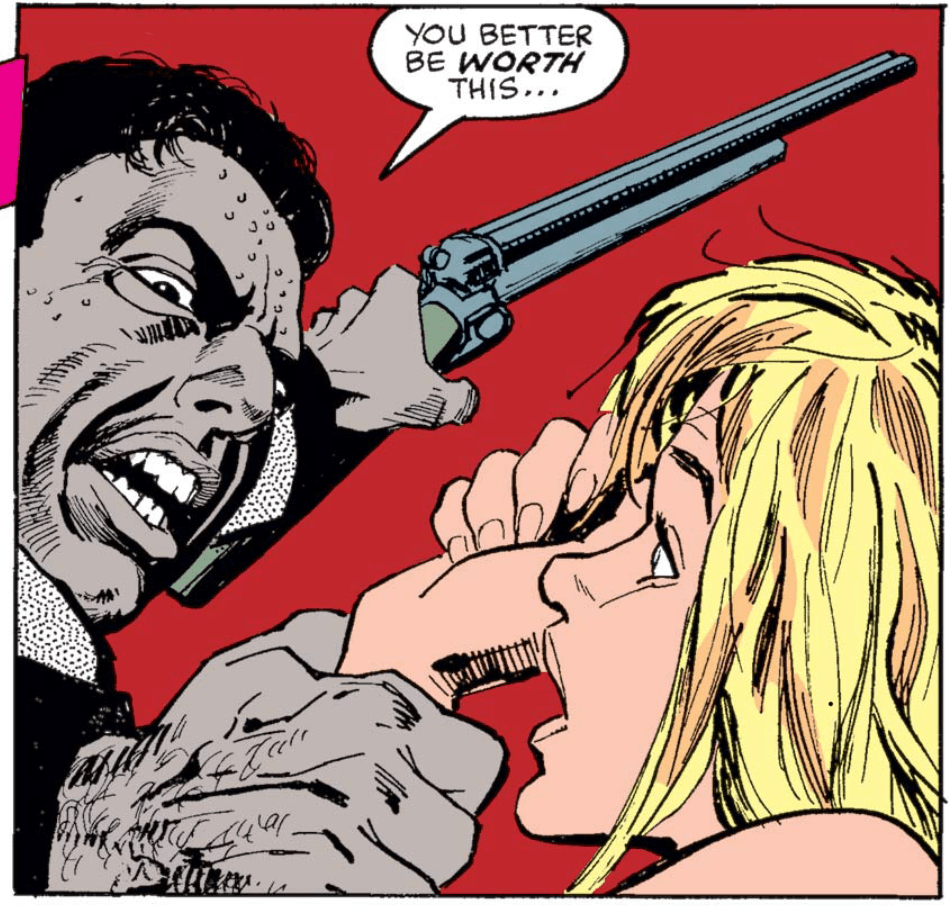

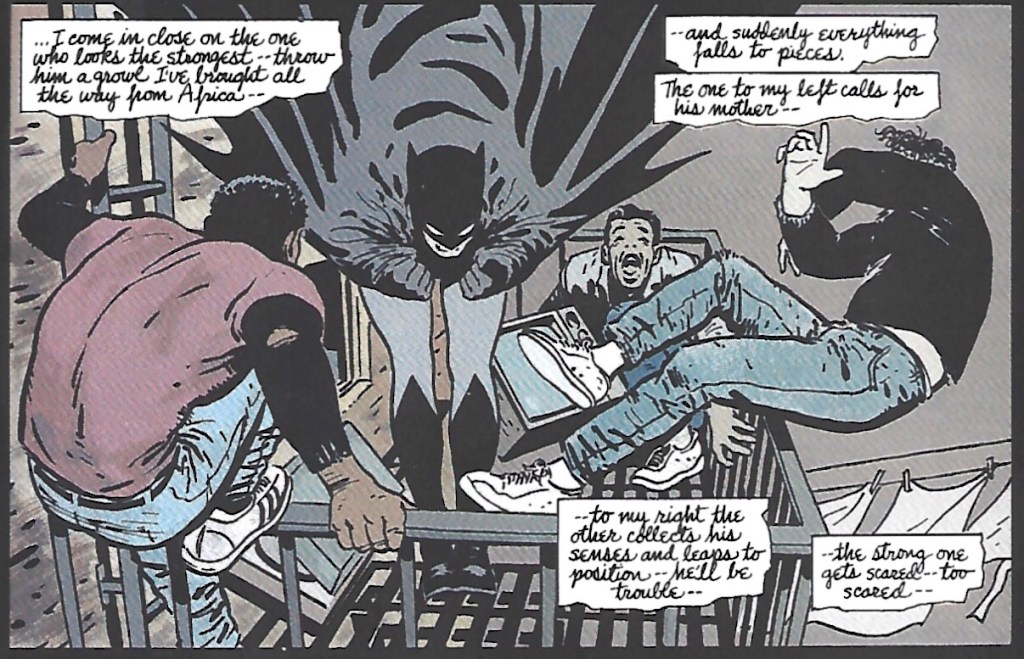

Linda McQuillan first appears in the Alan Moore stories of the 80s. Who, either born in Northern Ireland or with their roots there, would wrap themselves in a Union Jack? How could it be seen as anything other than the most appalling provocation? How could you not associate that flag in Northern Ireland with political dispossession, the corrupt RUC, the loyalist paramilitaries, the free hand of the British security forces?

Unless, as one of the interviewees in James Bluemel’s extraordinary documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland says, if you’re a Northern Irish protestant, you’re “more British than the British.” Is that we should think? Linda’s on the side of the security forces, the loyalist paramilitaries …? Or does she put on the flag because (cf. Captain Britain, in his Paul Cornell incarnation), she “wants to represent, like Steve Rogers did” – and somehow thinks, in a haze of naivete, that the Union Jack can represent both communities at once …? Is she somehow a bit like Sean Duffy, the Catholic cop in the RUC, in Adrian McKinty’s crime series?

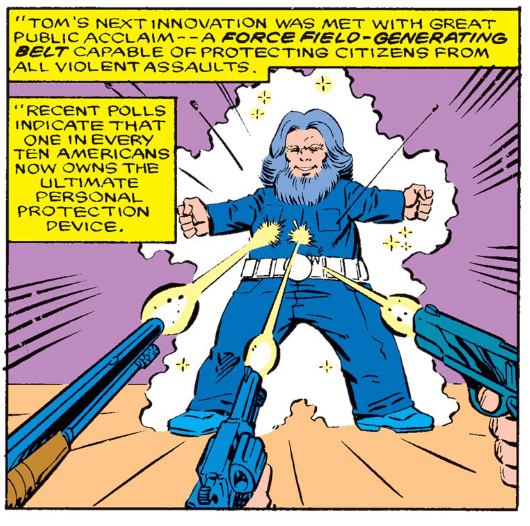

You can see how unfathomable and even absurd all this is. The absurdity is baked into Dave Thorpe’s abortive plan to “tackle” Northern Ireland in the early days of the revived CB. This plan was famously terminated with prejudice by Bernie Jaye, and in its place came the fantastically weak allegory, if it was even that, of the Rottenpasts and Coalitch. But imaging Captain UK as herself Irish shows just how crass Thorpe’s original question was: to ask, as he recalls doing, “What would Captain Britain have to say about the Northern Irish question” is to give CB the luxury of considering this tortuous, murderous legacy of colonialism as, precisely, a “question” – it’s only a question if you don’t have skin in the game. It’s a “question” if you’re quaffing brandy with the chaps at the club, and the real consequences of this legacy never come anywhere near you.

More to come, you lucky bastards.